|

| A Winnipeg roundabout |

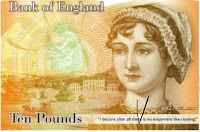

In my long life, I have found that things happen inside every institution that people on the outside just wouldn't believe. In the photo to the left, the ugly brick and concrete blob, surmounted by ugly traffic signs inscribed with ugly graffiti, is a Winnipeg roundabout. It has replaced a set of four-way stop signs. It’s not exactly the

grand rond-pont at the Place de l’Etoile in Paris, is it? Nor is the structure atop the blob the Arc de Triomphe.

Roundabouts are commonplace in Europe, ideal for dispersing lots of traffic at major intersections. At the Place de l’Etoile, for example, twelve avenues lead into the

Place and distribute traffic which circles the Arc de Triomphe until it manages to find an exit. It’s an unforgettable driving experience!

I don't think roundabouts have really caught on in Canadian cities. In Victoria, we have one on the Pat Bay Highway near the airport, which was very confusing to motorists at first, and took some getting used to. It is said that one driver went round and round in circles for several days, unable to find his way out. Winnipeg never had a roundabout at all. Its most famous intersection, Confusion Corner, where six roads meet, would have been well served with one, but Winnipeggers were confused already, and the authorities worried that drivers wouldn't have been able to handle it.

The great Canadian traffic controller is the four-way stop. It is perfect in every way, and typically Canadian. It is polite. At the intersection of two streets in a residential neighbourhood, stop signs halt the traffic on all sides. Cars stop and cross the intersection in the order of their arrival. Each driver observes to the split second whether he or she arrives before the car on the left or right, and waits or moves across, accordingly. It sometimes happens that two drivers arrive at precisely the same time, and there's a little hesitation and perhaps a false start, but all is resolved with a friendly wave. Yes, there is the occasional yob, who cheats and doesn't wait his turn, but he's probably from another country. Undoubtedly, the four-way stop sign is one of the reasons we have less road rage in Canada, for it calms the driver. Slow down, come to a complete stop, pause for reflection, and calmly cross the intersection.

The four-way stop sign is perfect in every way. Why mess with it?

The four-way stop signs in the quiet residential neighbourhood where I am staying were working perfectly well. They controlled and calmed the traffic. They slowed the cars down in an area where people were walking and children were playing.There were no collisions. Pedestrians crossed in safety. Nobody complained. They were perfect in every way. So why mess with them?

Well, in every institution, if things are working perfectly well, a new administrator isn't going to make a name for himself, since he wasn't responsible for things working perfectly well. So, he has to make a change, to innovate. And then things don't work perfectly well any longer. This happens in education all the time. And I suspect that this is what happened to the Winnipeg four-way stop signs.

Now, many of the four-way stop signs in the quiet residential neighbourhood where I am staying have gone, replaced, at huge expense, by ugly concrete blobs, around which cars swerve as they cross the intersection, or hug, as they turn tightly to the left.

Every vehicle has a turning circle, which determines how tightly it can turn. Someone must have forgotten to calculate whether vehicles with a wide turning circle could turn to the left around the roundabout. They can't. (Just as someone forgot to calculate whether the Bombardier trains could fit into

French railway stations. They couldn't.) A larger vehicle, such as an RV or delivery van, perfectly legitimate traffic in a residential neighbourhood, can not make the left turn in one go, and has to stop, back up a little, and then move forward again to leave the roundabout.

|

The roundabout at the Place de l'Etoile

where traffic circles the Arc de Triomphe |

But if the intersection is clear, instead of stopping as they were wont to do, giving a friendly wave to the driver on the left or right, the cars barely slow down, give a little wobble to the right as they pass the dollop of concrete, and then speed on, arriving at the destination a few minutes earlier than before. And the neighbourhood is less calm and less safe. Such is progress!